In the annals of history, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) stands as a monumental force in global trade and colonial expansion. Even though they were the largest trading company of their time, the cryptography they used was almost non-existent.

Nevertheless, there is a testimony of at least one encrypted message that even traveled 10,000 km. I, together with the Dutch Historian Jörgen Dinnissen, decrypted the letter, which can be still found in the National Archives of the Netherlands in The Hague. This blog post looks at this captivating piece of this hidden history: an encrypted letter from the VOC era. It gives an insight into the secret communications of the VOC in the 17th century.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC)

The United East India Company, known in Dutch as Verenigde Oost Indische Compagnie (VOC), existed from March 20, 1602, to December 31, 1799. As the largest private company of its era, the VOC’s scale and influence were comparable to modern giants like Walmart, Amazon, or Apple. At its peak, the company boasted over 150 ships, 200-250 locations across Asia, and about 20,000 employees. It held a monopoly on Asian trade, particularly in spices like nutmeg, mace, and cloves. The VOC wielded immense power, capable of waging war, negotiating treaties, and establishing colonies. The “Lords Seventeen” (Heeren XVII) were the governing body of this monumental trading empire.

Rijckloff Van Goens

Rijckloff Van Goens, born in 1619 and passing in 1682, was a pivotal figure in the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He notably served as the Governor of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) twice between 1662 and 1672. Renowned for his diplomacy, Van Goens rose to prominence in Batavia (now Jakarta) by age 37.

In 1655, his strategic plans for Asia were approved by the “Lords Seventeen” (leading board of the VOC) in Amsterdam, leading to successful conquests in Northwestern India, Ceylon, and Southern India by 1658. His 1663 conquest of Cochin in India secured a vital region for pepper trade. By 1674, the VOC, under his leadership, controlled Ceylon’s coast while the inland was governed by the King of Kandy.

Dutch Ceylon and the Island Ramanacoil

Dutch Ceylon, established in present-day Sri Lanka by the VOC from 1640 until 1796, was a key governorate of the Dutch colonial empire. The Dutch captured most coastal areas but were unable to control the Kingdom of Kandy in the island’s interior. Initially, the Dutch were invited by the Sinhalese king to assist in fighting the Portuguese, which led to their capture of maritime provinces and establishment of control. Galle served as the capital of Dutch Ceylon initially, shifting to Colombo in 1658. Dutch rule in Ceylon concluded in 1796 following the British takeover, influenced by geopolitical shifts in Europe.

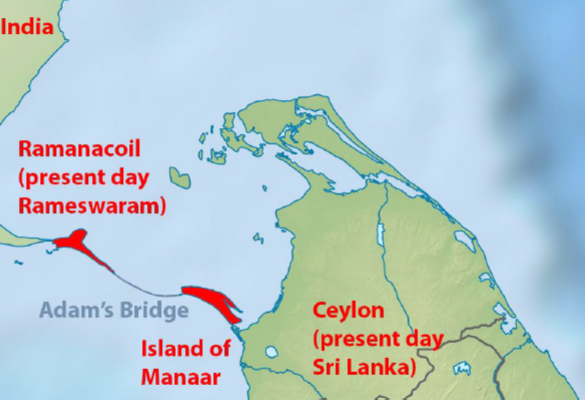

The island of Ramanacoil, known today as Rameswaram, is situated off the mainland of South India. It is historically significant due to its connection with the Island of Manaar through Adam’s Bridge, a natural chain of limestone shoals. This geographical feature has been of interest for its historical and cultural connections, forming a link between India and Sri Lanka.

In 1674, during the Franco-Dutch War (1672-1678), Rijckloff Van Goens had ambitious expansion plans for the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Asia. He made up a ‘wish list’ of territories he wanted to conquer. These ambitions took place against the backdrop of the war in which the Netherlands and the VOC were fighting against France, England and several other countries.

The Journey of an Encrypted Letter

In a time when communication was fraught with risks of interception and misinterpretation, an encrypted letter on this topic (conquering new land) from Rijckloff Van Goens embarked on a remarkable journey spanning approximately 10,000 kilometers. Dispatched from Ceylon, a crucial VOC stronghold of the time, the letter was carried by Van Goens private secretary Leeuwenson. Accompanied only by a single soldier for protection, Leeuwenson carried both the letter and additional memorized information for the Lord Seventeen. The journey took them 243 days. Van Goens, wary of the ongoing war against England and Spain, chose this over the sea route to ensure the message’s safety. To avoid detection, Leeuwenson and his companion disguised themselves in oriental clothing, blending in during their arduous and secretive journey (see first image of this blog article to get an idea how they may have looked like).

In the letter carried by Leeuwenson, Van Goens outlined significant military ambitions. He demanded the conquest of all Sri Lanka, Ramanacoil Island, and surrounding Indian coastal areas. To achieve this, he requested an additional 1,000 soldiers, planning to employ the successful tactics he used in 1655. Leeuwenson not only delivered this encrypted letter to the Lords Seventeen but also relayed additional memorized information. However, despite Van Goens’ efforts and strategic vision, the Lords Seventeen rejected his proposal. The VOC had shifted its expansionist strategy to a more cost-effective approach, focusing on reducing the number of locations and soldiers.

The Letter and Its Decipherment

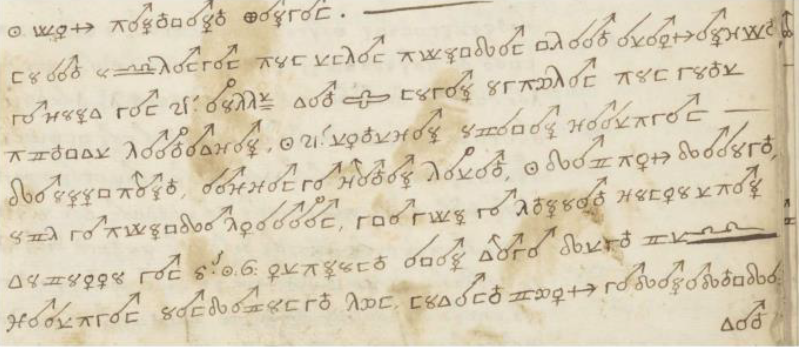

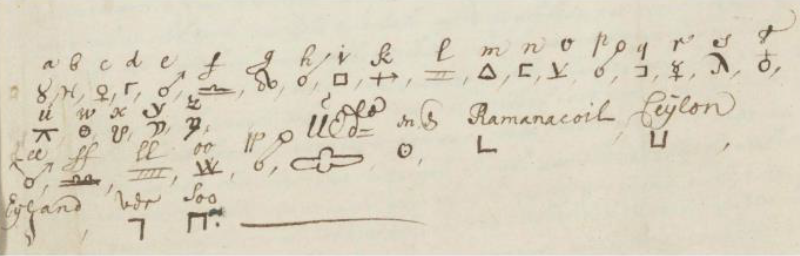

Today, the intriguing letter sent by Van Goens is preserved in the National Archives in The Hague. This historical document, spanning 46 pages, is mostly encrypted using alchemical and astrological symbols. Fascinatingly, a copy of the key to this cipher is stored alongside the letter.

Students from the University of Uppsala transcribed the encrypted document, and my colleague Jörgen Dinnissen and I conducted a thorough cipher analysis, leading to publications in HistoCrypt [1] and the German computer magazine c’t [2]. We incorporated the key into CrypTool 2, facilitating an easy decryption of the letter, despite the transcription process being more time-consuming. The cipher, a monoalphabetic substitution cipher, omits the letters V and J and includes symbols for five double letters. Intriguingly, the words ‘CEYLON’ and ‘RAMANACOIL’ appear in the plaintext without corresponding nomenclature elements, hinting that Leeuwenson might not have crafted the key. Jörgen’s deeper analysis of the cipher elements offers further insights into this historical cryptographic puzzle.

References

You may read the English research article as well as the German article in the c’t. Also, here is a link to the cipher in the DECODE database.

[1] Dinnissen, J. & Kopal, N. Island Ramanacoil a Bridge too Far. A Dutch Ciphertext from 1674. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Historical Cryptology (HistoCrypt 2021) (pp. 48 57). 2021.

url: https://ecp.ep.liu.se/index.php/histocrypt/article/view/156

[2] Kopal, N. & Dinnissen, J. Konzerngeheimnisse – Entschlüsselt: Ein Brief der Niederländischen Ostindien-Kompanie. c’t 16/2022 p. 13. 2022.

url: https://www.heise.de/hintergrund/Kryptografie-Brief-der-Niederlaendischen-Ostindien-Kompanie-entschluesselt-7189157.html

[3] Record 1564 in the DECODE database. “The Ramanacoil Transcript”.

url: https://de-crypt.org/decrypt-web/RecordsView/1564

A YouTube Video About the Ciphertext

Of course, I also made a YouTube video about the ciphertext and its story :-). You can watch it here: